A Night With Mo

Climber or not, we all have something to learn from her story.

The sport of rock climbing is as much a physical and mental activity as it is a mentor. Teaching lessons applicable to one’s life off the rock, it ingrains the notion of hard work and determination, quick and adaptive thinking, and most importantly, it opens the gate to what one may think achievable for themselves, encouraging them to push the limit of what’s deemed possible.

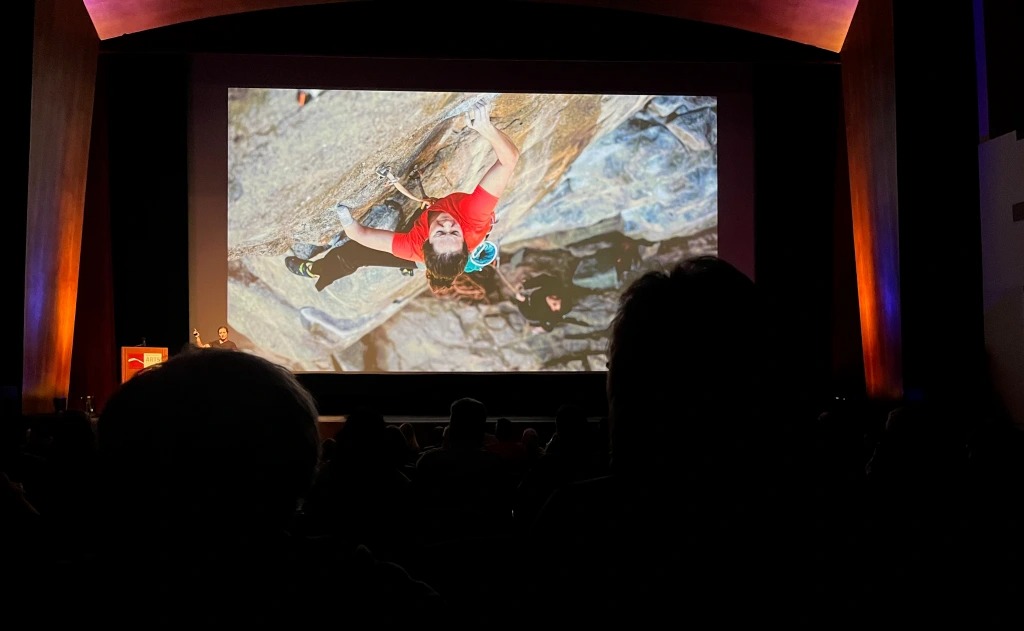

Coming to San Luis Obispo, as part of her national speaking tour with National Geographic, paraclimber and two-time world champion Maureen “Mo” Beck shared her story at the Performing Arts Center on May 1. Bringing together an audience of both rock climbers and non-climbers, as well as community members young and old, Beck took listeners on an exhilarating and humorous journey through her life, where she recounted narratives from childhood and the defining moments that have led her to where she is now.

Nature and sports have been a big part of Beck’s life since a young age, and having been born without her lower left arm, she learned the skill of adapting very quickly. She shared with her audience that she could “duct tape her way to a solution” in most scenarios, whether that be securing a canoe paddle or archery bow to her prosthetic hand during activities at sleep away camp, or wrapping medical tape to her stump when climbing to stop it from excessively bleeding on the rock.

For Beck, adapting also meant not letting others’ perceptions of her abilities get her down. But luckily, she got a kick out of proving people wrong. Playing soccer for many years but insisting on being the goalie, she started pushing the limits of what people believed she could accomplish, having only one hand.

And when it came time to try rock climbing for the first time— a sport understood by many as a two-handed activity— with her camp counselor ushering her to the nearest bench, telling her it was okay to “sit this one out,” Beck was even more ready to tie in and get climbing.

Getting to the top wasn’t the point. Up there, as Beck described to her audience, “it was just me on this rock and this piece of granite. It didn’t care that I was a 12 year old girl with an attitude. It didn’t care I was a 12 year old girl with a disability, It didn’t care. It was just a rock.”

This realization, that she could just ‘be’ and connect with the natural world on a level she had never been able to before, sparked an ever-growing passion for rock climbing that has led her to do amazing things.

As Beck began to find her place in the climbing community, she finally recognized that she was, in fact, disabled, and that it was not a bad word. During another crazy story Beck took the audience through, she detailed the time she was asked to climb at an adaptive ice climbing festival with a non-profit group called “Gimps on Ice.” Although a little skeptical, yet intrigued by the name, she went, and as she said, “I met this crew of people and there was something wrong with all of us. We were wonky. People were blind, they were missing legs, they were paralyzed and missing arms.” The level of psych and raw determination that these people had left Beck reveling at the fact that she too, was part of this ever-growing, strong community of rock climbers.

Beck was then driven to continue expanding her community of climbing friends and uplifting others with disabilities to push the limits, for she knew the dire importance that representation had for anyone doubting their abilities or trying to find their place in the world.

For example, it wasn’t until Kimber, a stranger to Beck at the time, who is missing her right hand, saw a photo of Beck with her makeshift “ice-ax arm” screwed into her prosthetic, that she realized that was possible for herself. Now, as Beck said, Kimber ice climbs all around the world. Beck also works with the Paraclimbing section of USA Climbing, a category for athletes with a range of disabilities, as well as with the adaptive climbing community, continuing to make a positive impact on others’ lives.

Throughout the night, Beck also detailed the growth and progression of her own climbing, recounting the years participating in paraclimbing competitions, winning two World Championships, one World Cup and eight National Championships, as well as going on an expedition-style trip of her dreams— and worst nightmares.

Meeting a fellow adaptive athlete, Jim, who had his left leg amputated following a fatal climbing accident, after he slid into Beck’s Facebook DM’s asking her to accompany him on a big trip, she said yes.

Even with a million reasons to say no, Beck committed to the unknown. After a year of training and fundraising, the pair made it to Nahanni National Park in the Northwest Territories of Canada. In such a remote area, with the closest roads being 300 miles away, Beck was forced to face her fears and look the peak, named the Lotus Flower Tower, with all of its 2,000+ feet of looming rock, in the eye.

With long approaches, horrible weather and gruesome climbing for 18 pitches, summiting was quite anticlimactic, as Beck recounted. But maybe, that is why the process of getting there, and the painstakingly difficult days leading up to it, are in turn the most valuable. It is there, Beck highlighted, that growth takes place.

“I think because everything went wrong, I learned even more,” Beck told the crowd.

Letting climbing be a source of knowledge, guiding her through the unexpected parts of life, Beck has learned to be mentally flexible. Because while set plans may fall through, or you’re forced to walk away from a climb unfinished, you can always look out at the view and acknowledge how far you have come.

Climbing has also revealed the balancing act of learning and acknowledging one’s limits while also pushing out of one’s comfort zone, for finding that perfect equilibrium, as Beck’s experiences have proven, get you out into the world and lead you to unforgettable places.

Climber or not, we can all derive meaning from Beck’s story and apply it to our own lives. Connecting with one another, and continuing to push the limits.

Cal Poly Climbing Club speaks with Beck after the show/Photo by Claire Griffith

Cal Poly Climbing Club speaks with Beck after the show/Photo by Claire Griffith

Post a comment